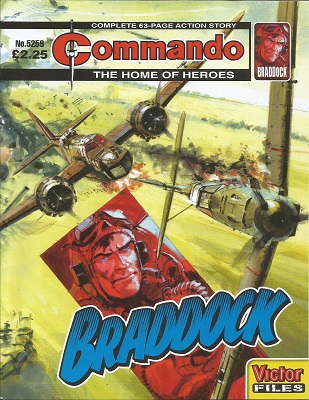

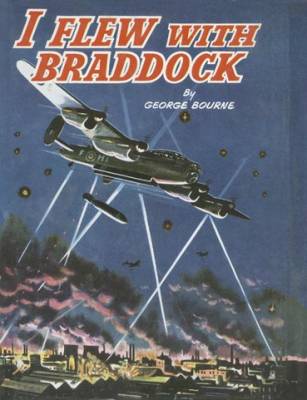

I FLEW WITH

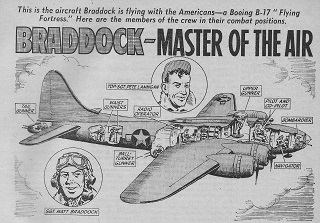

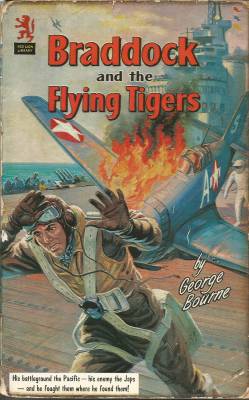

BRADDOCK (First series) The Rover from 2/8/1952 for 31 weeks

I FLEW WITH

BRADDOCK (First series) The Rover from 2/8/1952 for 31 weeksThe Hawker Hurricane - the RAF's forgotten fighter star of the Battle of Britain.

Matt Braddock or Biggles?

The rough working class bloke or the delicate posh one?

The "Other Ranks" or The Officer?

Braddock living where the work was or Biggles with the Mayfair flat?

Braddock the disregarder of rank and rules or Biggles where everyone knew their place?

Captain W.E. Johns or the anonymous author?

During the late 1950s and early 1960s I became aeroplane mad. This obsession was mostly fuelled by the adventure stories of Biggles and Braddock. I always enjoyed the two characters but it eventually occurred to me that they were very different characters and I started thinking about "class", status, lifestyle, etc.

Where were they born?

| Braddock From "Braddock and the Flying Tigers" page 42 – set in 1942 Holton took Braddock’s full names - Matthew Ernest Braddock, his birthplace as Walsall, and his age as 30………….. “ What was your mother’s birthplace?” snapped the lieutenant. “ I think she came from Salop,” said Braddock. “ Where?” exclaimed Holton. “ Just put Salop,” said Braddock……………. |

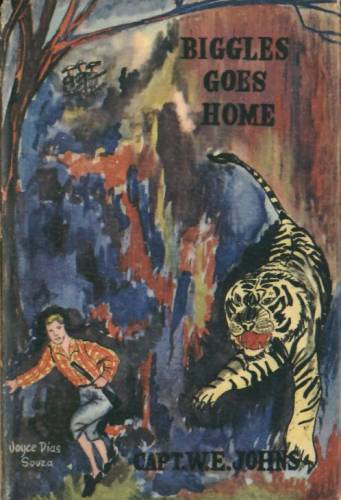

Biggles From Biggles Goes Home - Chapter 2 – A Tough Proposition Page 16 “TELL me, Bigglesworth, where were you born?”Air Commodore Raymond, head of the Special Air Police at Scotland Yard, put the question to his senior operational pilot who, at his request, had just entered his office. “That’s a bit unexpected,” answered Biggles, pulling up a chair to the near side of his chief ’s desk. “India. I thought you knew that.” “Yes, of course I knew. I should have been more explicit. Where exactly in India?” Biggles smiled faintly. “I first opened my peepers in the dak bungalow at Chini, in Garhwal, in the northern district of the United Provinces.” “How did that come about?” “My father had left the army and entered the Indian Civil Service. He was for a time Assistant Cornmissioner at Garhwal and with my mother was on a routine visit to Chini when, as I learned later, I arrived somewhat prematurely. However, just having been whitewashed inside and out, the bungalow was nice and clean, and I managed to survive.” |

Where did they go to school?

| Braddock From BORN TO FLY page 24 of The Rover from 30th Oct 1971 “I’ve come to join the Volunteer Reserve,” said Braddock. “No one was about, so I walked in.” “We don't take mechanics,” replied Butleigh. “Our business is to train pilots.” “That’s what I’m here for,” retorted Braddock. “If I don't go solo quicker than A. F. G. Carrington ” – he made a gesture towards the blackboard - “ you can give me the sack.”…………………. “ Occupation?” “I’m a steeplejack,” said Braddock. “How frightfully interesting,”, remarked Butleigh. “Where did you go to school?”

“I went to an elementary school near Walsall,”

Braddock answered. “I’m afraid that wouldn’t

measure up to the required educational standard,”

said Butleigh smugly. “Candidates must have received

an education up to the standard required for the From I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First

series) The Rover from 4/10/1952 “ Where did you to go school,

Braddock ?” he asked. “ That’ll take a bit

of remembering,” muttered Braddock. “ I went to

schools in Birmingham, Manchester, Glasgow, Liverpool,

Bristol, and Southampton. Oh, and I was forgetting - I

put in a few months at Northampton.” |

Biggles While living in India he was educated by a private tutor. At the age of 14 and a half Biggles was in England to attend Public School. He became a boarder at Malton Hall School in Hertbury. The school had previously been attended by his brother, his father and his Brigadier-General uncle. From - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_school_(United_Kingdom)

Public schools have had a strong association with the ruling classes. Historically they educated the sons of the English upper and upper-middle classes. In particular, the sons of officers

and senior administrators of the British Empire were

educated in England |

What was their lifestyle?

| Braddock From BORN TO FLY page 24 of The Rover from 30th Oct 1971 Braddock had put his motor cycle back on the road when he got work again. Before he had obtained this job he could not have spared one and eight pence for a gallon of petrol. He had made the machine himself from second-hand parts he had obtained for a few pounds. Braddock rode to a tiny house in Canal Road, where he boarded with Mr and Mrs Givens, both of whom received the old-age pension. |

Biggles From Biggles Hits the Trail - page 10 "Exactly fifty-five minutes later Biggles's Bentley pulled up with a groaning of brakes outside the small country station of Brendenhall." From Biggles Breaks the Silence - page 9 "The voice came from the other side of the room, where Sergeant Bigglesworth, head of the Department, was regarding the street below through the window of his London flat in Mount Street, Mayfair." Mount Street, London W1K - 2 bed

flat for sale - £4,950,000 in 2015 (zoopla) |

Boys turning into men......

| Braddock From BORN TO FLY page 22 of The Rover from 30th Oct 1971 ON an autumn morning in 1938 three men were working at the top of the new factory chimney at Billingham & Company’s works in Midhampton. The chimney, which was intended to carry away chemical fumes, soared to a height of 350 feet and there were many local arguments as to whether or not it was the tallest in the country…….. The face of a complete stranger

appeared. It was that of a young man of robust "I just need a job,” said

Braddock. “1’ve worked in general engineering,

l’ve done some bricklaying in my time and I can

drive a lorry.” Jack Foster was impressed by |

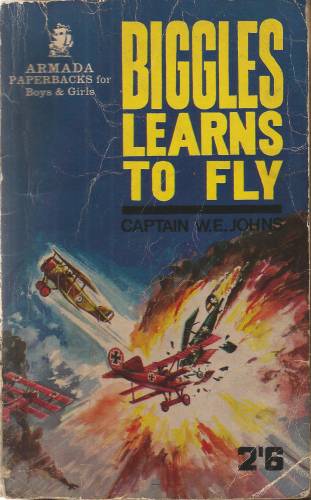

Biggles From Biggles Learns to Fly - page 7 There was little about him to distinguish him from thousands of others in whose ears the call to arms had not sounded in vain. and who were doing precisely the same thing in various parts of the country. His uniform was still free from the marks of war that would eventually stain it. His Sam Browne belt still squeaked slightly when he moved, like a pair of new boots. There was nothing remarkable or even martial, about his physique; on the contrary, he was slim, rather below average height. and delicate-looking. A wisp of fair hair from one side of his rakishly tilted R.F.C. cap; . now sparkling with pleasurable anticipation, were what is usually called hazel. His features were finely cut, but the squareness of his chin and the firm line of his mouth revealed a certain doegedness, a tenacity of purpose, that denied any suggestion of weakness. Only his hands were small and white, and might have been those of a girl. His youthfulness was apparent. He might have reached the eighteen years shown on his papers. but his birth certificate, had he produced it at the recruiting office, would have revealed that he would not attain that age for another eleven months. Like many others who had left school to plunge straight into the war, he had conveniently ‘lost’ his birth certificate when applying for enlistment, nearly three months previously. |

But all things must pass ......

| Braddock From Braddock and the Black Rockets “Matt Braddock, a national The event was fictitious as the

"death" was fake to cover up a secret mission

to prevent World War Three! "Old soldiers never die, they simply fade away". |

Biggles From Biggles: The Authorised Biography by John Pearson – page 310 " …… I was

surprised to hear that he was going to the Battle of

Britain anniversary celebrations, being held that year at

Tangmere. He'd never gone before, but several of the

former members of 666 were turning up, and he was invited

as a guest of honour. As part of the celebrations, a rich

American called Maberley had brought over a beautifully

restored Mark VI Spitfire from Texas. It was a rarity, of

course, a true collector’s piece, and, judging from

the photographs I saw, perfect in every detail.

Apparently, one of the young R.A.F. pilots had been

scheduled to fly the Spitfire at the head of the fly-past

of the latest British jets, and just before take-off,

Biggles was standing next to Algy on the tarmac,

examining the machines. No one will ever know what got

into him — or how he managed it. Presumably the

sheer temptation of that wonderful old aircraft standing

there, ready for take-off, was too much for him. A

momentary old man’s impulse, a brief resurgence of

his youth — or had he somehow planned this all along?

I wonder. He took everybody by surprise, including Algy.

The pilots were just about to board their planes, when he

darted forward, shouting, ‘Scramble, chaps!’

And before anyone could stop him, Biggles had swung

himself with practised ease into the Spitfire’s

cockpit, slammed back the canopy, and started up the

engine. It happened very quickly, and from that point

there was nothing much anyone could do to stop him. The

Controller did his best, of course (he was entirely

exonerated at the subsequent inquiry), but Biggles

totally ignored the poor man’s frantic messages over

the radio. All he replied was ‘O.K. 666. Prepare to

intercept the enemy. Large formations of Heinkels and a

pack of Messerschmitts coming in from northern France.

Fourteen thousand feet. Do your best, chaps!’ Then

the radio went dead, and the Spit?re slowly taxied past

the crowds, none of whom realised what was going on. He

made a perfect take-off, with the jets following him as

planned. From the ground the fly-past seemed immaculate,

with Biggles’ solitary Spitfire in the lead. Then

the crowd saw the Spitfire turn, sweep back across the

airport, flipping its wings in a salute, then climb

towards the sun, and the coast of France. And that was

the last that anybody saw of Biggles. |

Was Braddock "Officer Material"?

From I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series) The

Rover from 13/09/1952

I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series - repeat) The Rover from 05/04/1958

BRADDOCK MASTER OF THE AIR (Repeat of first series) The Rover and

Wizard from 04/02/1967

“ So far as aircraft are concerned, then, the squadron

is about finished,” Braddock said. “ There’s about

one machine left that’s fit to fly.” “It was an

expensive business last night,” Crosby said grimly."

“ Still,we’re not here to discuss the raid. Have either

of you considered taking commissions?” It was a question

that came as a surprise. He was looking at me, so I answered

first. “ It’s the first time I’ve been asked, sir,”

I said. “ When I joined up I was shot straight off to a

navigation school.” Crosby shifted his gaze. “ What

about you?” he asked Braddock. A grin appeared on Braddock’s

rugged face. “ I’d hardly be classed as officer

material, would I?" he said. “ No, I don't think I’d

like it.” “ You can’t think of things from a

personal point of view when we’re scrapping for our lives,”

Crosby retorted. “ A pilot of your ability, Braddock, might

very soon be leading a squadron. “ You, too, Boume, might

easily become a squadron navigation officer. I put it to you that

you would be of more use to the Service and to the country in

such a capacity than as mere members of a crew. “ I ’d

like you to think it over. I’m not asking for a decision now.

Brood over it a bit and then let me know if I can put your names

forward.” His telephone rang and we went out. There was a

scowl on Braddock’s face as we walked away. “ No,

George,” he said abruptly, “ I can’t see myself as

an officer.” “ There’s something in what he said,”

I replied. “’There’s a war on and we can’t

please ourselves.” "I’ll think about it,”

Braddock answered brusquely.

From I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series) The

Rover from 27/09/1952

I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series - repeat) The Rover from 19/04/1958

BRADDOCK MASTER OF THE AIR (Repeat of first series) The Rover and

Wizard from 18/02/1967

BRADDOCK usually had no difficulty in making up his mind

about anything, but now there was uncertainity on his rugged face.

"You've been straight with me, and I'll be straight with you,"

he said gruffly. ” I have to go my own way. I can get on

with real flyers like yourself, but these red-tape types get my

goat.“ Crosby laughed. He was a regular officer of the best

type, devoted to the Service. “ Yes, I’m quite sure

that at a ceremonial parade you’d be the one man out of step,”

he said and the remark brought a grin to Braddock’s face.

“ When you came here I thought you were one of these awkward

characters. “Your disregard of discipline on the ground

annoyed me agreat deal. But I’ve had reason to change my

mind. The moment you’re off the ground, you’re the

tightest disciplinarian I’ve seen. “ In every detail

which concerns flying, you’re as meticulous as a Drill

Sergeant on the parade ground.” “ Well, it’s

only common-sense to leave nothing to chance,” grunted

Braddock. “ What’s more you have a tremendous capacity

for leading and inspiring others in the air,” Crosby

exclaimed. “ It’s my honest opinion, speaking as man to

man, that the Service can ask you to undertake the

responsibilities of leadership instead of carrying on as, shall I

say, a lone wolf.” “ Supposing I say yes, what will

happen next?” Braddock demanded. “ You’d skip a

stage or two. You wouldn’t find yourself at an Initial

Training Wing,” smiled Crosby. “First you’d be

interviewed by the Selection Board which, of course, would have

your record in front of it. Then you’d take a short officer’s

training course.” “ I’ll sleep on it,”

answered Braddock. “ I’ll give you my answer tomorrow.”

“ That goes for me, too,” I exclaimed. “ Fair

enough,” said Crosby. Braddock gave me a wry grin when we

got outside. “ He may be right, George,” he muttered.

“ I’ve never thought about wearing an officer’s

rings but if I can help others to fly their planes right, maybe I

should do as he says. Still, we’ll see.”

From I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series) The

Rover from 4/10/1952

I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series - repeat) The Rover from 26/04/1958

BRADDOCK MASTER OF THE AIR (Repeat of first series) The Rover and

Wizard from 25/02/1967

SELECTION BOARD

At three o'clock that afternoon a clerk opened the door of an

ante-room in the admitnistration block at Tungmore. “

Sergeant Braddock!” he called out. I pointed at Braddock’s

tunic as he stood up. “ Your top button’s undone,”

I said. Braddock did not bother about fastening it before going

into the room where the selection board awaited him. With five

other strained-looking men I settled down as best as I could to

wait my turn. What happened in the room I learned afterwards. The

clerk told me some of it and Braddock dropped other bits from

time to time. The board was presided over by Air Commodore

Framley. The members with him were Group Captain Riggs, Squadron

Leader Santon, and Mr Wiggins from the Air Ministry. “ We

understand you had some excitement on your way here, Sergeant !”

he exclaimed. Braddock put his hands behind his head and leaned

back comfortably. “ Yes, it was lucky for us that the German

was a prune,” he said. Framley shuffled his papers. “

We have your war record here, of course,” he remarked.

“ Extremely creditable it is, too. But you'll understand

that we have to make up our minds as to whether or not you would

make a good officer. It carries responsibilities, Braddock. An

officer has to set an example. He has to be able to obtain

respect from the airmen. High standards of conduct and bearing

are expected from him.” “ You haven’t mentioned

flying,” said Braddock. “ Isn’t that important ?”

Framley frowned. “ That’s taken for granted,” he

said huffily. “ I just wondered why you didn’t mention

it first,” remarked Braddock. Riggs made his voice heard for

the first time. “ Where did you to go school, Braddock ?”

he asked. “ That’ll take a bit of remembering,”

muttered Braddock. “ I went to schools in Birmingham,

Manchester, Glasgow, Liverpool, Bristol, and Southampton. Oh, and

I was forgetting—I put in a few months at Northampton.”

“You jumped about a bit, didn’t you ?” smiled

Santon. “ Dad was a boilermaker, and he had to go where

there was work,” explained Braddock. Framley kept his gaze

on his papers. “ I see that on enlistment you described

yourself as a steeplejack,” he said. “Yes, it’s a

job where bosses don’t worry you much,” replied

Braddock.

STARTLING NEWS

Two buff envelopes I were delivered to Braddock and me in the

morning. . . “ In these are the decisions of the selection

board. They haven't wasted much time,” I said. Braddock

stuck his thumb under the flap of the envelope and jagged it open.

He started to read aloud; “' ‘ With reference to your

application for a commission, I am directed to inform you that it

is with regret:-’ ” He grinned broadly. “ Turned

down,” he said. “ Just as well !” I opened my

letter. It was to the same effect. I was going to stay a sergeant..............

Kempsey answered a phone call with a brisk, “ Yes, get cracking,” and then looked at us again. “ I’ve some news for you,” he said. “ You will both be gazetted as pilot-officers this week.” I stared at him in blank amazement. “We’ve just. been turned down by the board, sir!” I exclaimed, and Braddock drew the buff sheet of paper from his pocket. Kempsey smiled. “ My information comes from much higher up,” he said. “ I had a word on the phone about it, and was told that your promotions were made largely on the recommendation of Dr. Edward Cassidy, the physicist.” I’d heard the name of Cassidy. He was one of our top boffins, one of our greatest radar scientists. But, so far as I knew, I’d never met him, and that made the news startling. “ What have we done to him ?” Braddock gasped. “ He was a passenger in the Anson you landed on one leg,” answered Kempsey. “ Oh, the chap with the bowler,” exclaimed Braddock. “ I don’t think so,” replied Kempsey. “ I’ve seen him frequently and he always wears a cap.” Braddock uttered a chuckle.

From I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series) The

Rover from 25/10/1952

I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series - repeat) The Rover from 17/5/1958

BRADDOCK MASTER OF THE AIR (Repeat of first series) The Rover and

Wizard from 18/3/1967

Goff was talking to the Adjutant, Flight Lieutenant Barlett

“’I shan’t be giving Braddock a recornmendation"

he said. “He talked a lot of wild stuff after my lecture.”

He gave Barlett who had the reputation of being a strict

disciplinarian, an account of what had happened. "You ought

to have shut him up,” "Barlett snapped. “We don’t

want him putting such ideas in the heads of other cadets.”

“I closed down as soon as I could,” Goff said. “But

he showed that he isn’t officer material.” “ The

Commanding Officer, unfortunately, won’t see eye to eye with

you,” stated Barlett. “ Ever since Braddock fetched

that Spitfire off the sandbank, he regards him as being in a

class by himself.” It was a strange position. Braddock did

not want to be an officer." Many members of the staff, like

Goff, thought that he wasn’t the type to be an officer. But,

at the top of the tree, high-ranking officers were pushing him

forward.

From I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series) The

Rover from 8/11/1952

I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series - repeat) The Rover from 31/5/1958

BRADDOCK MASTER OF THE AIR (Repeat of first series) The Rover and

Wizard from 1/4/1967

“ I’ve made up my mind,” he said. “ I’m

not going through with this course. It'll waste more time and, as

I’ve said before, I don’t fancy being an officer.”

“ I understand you’ve taken great exception to the

Passing Out ceremony,” exclaimed Wallasey. “ Are you

going on with it?” asked Braddock. “ Of course we’re

going on with it,” said the C.O. sharply. “ But that’s

besides the point. You baffle me, Braddock. You showed

outstanding qualities of leadership during that raid last night

and such are needed in command of our sections and squadrons. I'm

still convinced that it's your duty to undertake these

responsibilities.”

“No,” replied Braddock. “I'll stay as a sergeant.

I'll get back where I belong - in the air.” “ That’s

how I feel, too,” I said. The C.O. gave in grimly. “I’ll

see you are returned to a holding squadron as soon as possible,”

he said and curtly concluded the interview.

Braddock had a broad grin on his face when he got outside the

room. “George, that’s a load off my mind,” he

chuckled. “ I’ll never: be talked into going into this

officer lark again.”

I’m not keen on gongs.......

From I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series) The

Rover from 20/09/1952

I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series - repeat) The Rover from 12/04/1958

BRADDOCK MASTER OF THE AIR (Repeat of first series) The Rover and

Wizard from 11/02/1967

SHOCK FOR BERRICKER

Then the All-Clear was given and training resumed. Flight

Lieutenant Berricker was the duty officer in charge of flying. He

was in his room in the control tower with Group Captain Crosby

when Flight Sergeant Hampton came in and saluted. “ I’ve

made an examination of the Lysander, sir,” he reported.

“All guns have been fired. As a matter of fact, they’re

still hot.” “What have those fellows been up to ?”

Crosby exclaimed. “ Braddock told Gooley they had been

stooging around,” said Berricker harshly. “ You’ll

have to come down on them hard, sir.” The phone buzzed.

Berricker picked up the receiver. “ This is Fighter Sector,

Intelligence Officer,” announced the caller. “We are

trying to trace a Lysander which has been flying south of

Buckworth.” “ I’m sorry to say a Lysander from

here has made an unauthorised flight,” answered Berricker

pompously. “ The pilot is under close arrest.” “

What?” gasped the Intelligence Officer. “ He is under

close arrest,” repeated Berricker, thinking he had not been

heard. “ You’ve arrested him !” shouted the

Intelligence Officer. “ He’s shot down two Junkers,

damaged another so that it made a forced landing, and put a

Messerschmitt into a rookery.” Berricker nearly baled out of

his chair. “ We’ve heard nothing about it,” he

bleated. “Who was the pilot?” demanded the Intelligence

Officer. “ Er —— Sergeant Braddock,” gasped

Berricker. “ Sergeant Boume was with him.” “ By

jove, yes, I should have recognised the Braddock touch,”

exclaimed the Intelligence Officer. “ Thank you! You’ll

be hearing from us again. The Air Officer Commanding Group wants

full information as soon as possible.” I got a description

of this incident from a clerk on duty. Apparently Crosby suddenly

let out a tremendous guifaw, While Berricker’s face was as

red as the back of his neck. “ You’d better hurry up

and remove Braddock and Bourne from Gooley’s clutches,”

the Station Master said. It was a flabbergasted Gooley who let us

out. The Group Captain sent for us late in the evening. “

News has just come through to me that both of you have been given

the immediate award of the Distinguished Flying

Medal,” he said as he stood to shake hands

with us. Braddock frowned. “ Do we have to take it ?”

he asked gruffy. “ It’s a great honour,” ex

claimed Crosby. “ I know, but I’m not keen on gongs,”

growled Braddock. “ So many who earn ’em don’t get

’em. Some who’ve never earned ’em do.” “

In this case I feel that no mistake has been made,” said the

Group Captain bluntly. “ Now, I’m going to admit that I’m

just beginning to understand you, Braddock. I realise that you’ve

no use for red tape, but I’m also convinced that the Service

doesn’t possess a better pilot. Your abilities shouldn’t

be restricted by a sergeant’s stripes, and I want to urge on

you again and on Bourne that it’s your duty to allow me to

put your names forward for commissions.” He looked at us

inquiringly in turn. “ What do you say?” he asked.

“ Will you let me recommend you as officers?”

Braddock and the Thunderbirds - The

Rover and Wizard from July 31st1965

“ On leaving here you will report next door to the

tailor," Wally instructed us. “ This station may be out

in the wilder-ness, but we keep a good standard of discipline.

‘Week day parades are in denims, but on Saturday mornings

you will turn out for inspection in serge and with web belt

blancoed and brasses shining— understand ?” “ Ugh,”

said Braddock. “ That is not an answer, my man,” rasped

Wally. “But 1 take it you understand. Are you entitled to

any campaign ribbons or decorations ? If so, you will draw them

now for the tailor to sew on while fitting your uniforms.”

SHOCK FOR SOAMES

He stared at us ques-tioningly and became annoyed at not getting

an immediate answer. Campaign medals had by this time been issued

for service in certain theatres of war. Braddock and I were

obviously too young to have earned any of the pre-war variety.

But Wally knew we had been on our way home from the Far East so

he naturally expected us to say we were entitled to the 1939-45

Star. “ Let’s be hearing from you,” Wally snapped.

“ You, Sergeant Bourne-—what about it ?” “The

’39-45 Star,” ,I said reluctantly. “The D.F.M. as

well, I suppose.” "‘ The Distinguished Flying

Medal !” gasped Wally. He recovered quickly and gazed

sternly at me. “You understand that we shall be able to

check this in a week or so when your papers arrive here?” he

rasped. I told him the award was recorded in my papers and Wally

became almost friendly to me. He told the Q.M. to issue me with

three inches of the ribbon and then he turned to Braddock and

found himself confronted by a black scowl. Braddock said

irritably that he never bothered wearing ribbons. “They make

me feel like a blooming chocolate box soldier,” he growled.

“ Besides which I don’t feel right going round

plastered with glory when so many men have done as much and more

than me and not got a sausage for it.” “ Your feelings

do you credit, Sergeant Braddock,” said Wally with heavy

sarcasm. “ But orders is orders. What are you entitled to—the

1939-45 Star ?” “ All right, since you are making such

a big thing of it,” said Braddock, shrugging. “The 1939-45

Star—also, the Victoria Cross and bar, and the Dis-

tinguished Flying Medal and bar. There are a few others, but they’re

foreign decorations, and King’s Regulations don’t

insist on my wearing them.” There was a sort of hush in the

store when he finished speaking. Everybody I could see had

stopped doing what he had been doing and was staring at Braddock.

One man had frozen with a mug of tea halfway to his mouth and as

he stared the mug tilted and tea began to slosh out with - out

his appearing to notice. “ Omigorsh!” mumbled Wally

Soames. I have often wished I could have taken a picture of Wally

at that moment. His mouth hung open and his eyes seemed to have

slid a quarter of an inch out of their sockets. Only his waxed

moustache saved him from being a dead ringer for a dead codfish.

Who were the Authors?

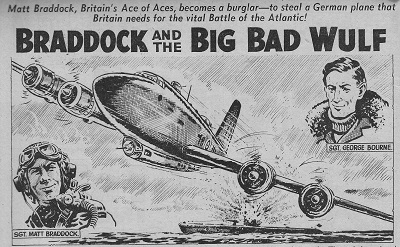

| Braddock Matt Braddock VC - originated in the D C Thomson comic "The Rover" and the author was given as "George Bourne". The actual authors were the D C Thomson staff writers who would turn their hand to several different characters as required. The main writer was Gilbert Lawford Dalton who was born in Kidderminster in 1903, the son of a journalist. His first job was with the Coventry Evening Telegraph and became a part time writer for various DC Thomson comics. In 1936 he became a full-time author. He was reputed to write up to a million words per year. Dalton settled in Leamington Spa after war service, moving to the South Coast in 1958. He died in 1963 at Weymouth. Birmingham born Alan Hemus (1925-2009) wrote later Braddock stories. More details of the stories below...................... |

Biggles James Bigglesworth DSO MC (or Biggles) - was featured in magazines and almost a hundred books by Captain W.E. Johns - published between 1932 and his death in 1968. As Biggles and W.E. Johns are well documented I will do no more than point you to........ |

I FLEW WITH

BRADDOCK (First series) The Rover from 2/8/1952 for 31 weeks

I FLEW WITH

BRADDOCK (First series) The Rover from 2/8/1952 for 31 weeks

I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (First series - repeat) The Rover from 22/2/1958 for 31 weeks

BRADDOCK MASTER OF THE AIR (Repeat of first

series)

The Rover and Wizard from 24/12/1966 for 31 weeks

Also see my Flickr album - Matt Braddock VC - boys comic stories

| The Rover - 22nd. Feb

1958 - Page 142 SERGEANT-PILOT

MATT BRADDOCK, V.C. and Bar, was one of the greatest

airmen of the Second l’m Sergeant George Bourne. I did my training in

navigation, |

the sergeant policeman de- manded. ‘ “ With my cap,” growled the sergeant-pilot. “ I’ve only got a railway ticket.” The sergeant took out his notebook. “ Name ?” he demanded. “ Braddock,” drawled the pilot. , “Number?” snapped the sergeant. “ How should I know ?” muttered Braddock. ‘The policeman thrust his notebook back into his pocket. “ Fall in,” he barked. “ You’re under arrest.” Braddock uttered a scoffing laugh. “ Come on,” snarled the sergeant. “ Quick march---” Braddock slung his kitbag on to his shoulder. It could have been accidental, but he caught the sergeant a resounding slap on the side of the head and knocked his hat off". The policeman looked as if he were going to explode from the violence of his emotions as he picked up his hat. He closed in on Braddock with his comrade. Braddock turned and winked at the onlookers. He made no attempt to keep in step as they marched him away. “He’s for it,” remarked a corporal. “ They’ll have him for every crime in the book-——” The gates rattled open and there was a rush for the train. I was out of luck. The train was so crowded that the best I could |

do was stand in the corridor

of a first-class coach, mostly occupied by officers. I was leaning out of the window watching the platform scene when a running figure burst through the gateway. It was the sergeant policeman. He legged it wildly towards the guard who was getting ready to wave his flag. He reached the guard and pointed back agitatedly towards the entrance. I thought that at least an air-marshal was on his way, but it was Braddock who ambled on to the platform. His hands were in his pockets. Behind him came the other policeman carrying the kitbag. While the guard and plat- form inspector were blowing their Whistles, Braddock sauntered along the train. He stopped opposite me. It was the first time I'd really seen him face to face and it was at that moment I became aware of his amazing eyes. I suppose you would have called them blue, but it was almost as if a light were shining through them, for they were astonish- ingly luminous. His chin was strong. His mouth was big and full lipped. The nose had a distinct twist across the bridge from an old fracture. I opened the door for him. He took his kithag from the policeman. “ So long, suckers !” he said. He got into the corridor and I pulled the door shut. The train immediately began to move. He peered into a com- partment in which there were two group captains, a colonel, a major, and two vacant seats. He pulled the corridor door open, entered the compartment, heaved his kitbag on to the rack and sat down. Then he gestured me in. “ Take the weight off your feet,” he growled. I’d come down from Scotland and was train weary. I went in and sat down. The major glared at us. “This is a first-class com- partment,” he snapped. Braddock yawned. “ I can read,” he said. The rnajor went red with indignation. “ I’m ordering you to get out l” he snapped. Braddock stretched his legs. “ When did you buy the railway ?” he inquired. |

The maior shot an infuriated glance at him. The group captains shifted uncomfortably. “ I shall report you to your commanding officer for dis- obeying an order and for insolence,” the major rasped. “ What’s your name?” “ Rhymes with haddock- Braddock!” The two group captains both gave a start. They looked at each other and then at Braddock. As the train roared under a bridge, one of than spoke to the major. I could not catch what he said, but the major didn’t have another word to say. In evident confusion, he opened a newspaper and hid himself behind it. Braddock winked at me and then put his head back and closed his eyes. The train put down most of its passengers at Colchester. Braddock and I were left with the compartment to ourselves. I took out my cigarette case. I did not smoke a great deal, iust now and then. As I opened it, I became aware that Braddock was gazing at me. I was going to offer him a cigarette but he spoke first. “ Smokings no good for you,” he said curtly. “ Put your fags away.” I was too taken aback to protest, and he added, “Bad for your eyes !" I shut the case and returned it to my pocket. ' Going to Rampton ?” he asked. " Yes !” I replied. “ So am I ! Lousy hole. Used to be full of spit and polish wallahs, sort of twirps who thought you couldn’t fly a plane unless you’d had your hair cut and your buttons polished.” Braddock’s lips took a sardonic droop. “ Ha, ha, that’s where I got kicked out.” “ Kicked out ?” I echoed. “ I was a week-end flier in those days,” explained Brad- dock, “ and we went there for a course. I lasted about twenty- four hours. Then they pushed me out.” I saw a dot in the sky and peered out at it. Braddock followed my stare. The aircraft was no more than a speck. “ Fairey Battle,” he said. Braddock was right though more than a minute elapsed, with the plane approaching us, before I was able to identify it for myself. |

| The Rover - 22nd. Feb

1958 - Page 143 BRIEFING FOR BOUSTRECKE. BRIEFLY, what was happening |

Muddling through,‘ but

that’s what we have to do. There’s a job to do today and that’s Why you’re here for briefing——-—” The door opened. I saw Pit- cairn frown. It was Braddock who strolled in. He shoved the door shut with his foot and sat at the back. Pitcairn reached for a pointer and there was a rustle of maps. Taylor turned. and beckoned for me to bring my chair up to his. As I moved, I looked round. Braddock wasn’t bothering to open a map. ’ “ There’s some very grave business on the right-flank of our rear-guards,” explained the Squadron Leader. “ Reports have reached us within the past half — hour that a Panzer division is concentrating in this area-—” His pointer moved to the wall map. “We have nothing to stop them with—-except water. If we can demolish the lock gates at Boustrecke, here, the Waters will be released and flood the low-lying ground between the rearguards and the Panzer |

blinked and yawned. “ Stuffy in here, isn’t it ?” he said. “ So that’s Braddock, is it ?” muttered Taylor. “ One bomb Braddock !” “ One bomb ?” I said. “ The story goes that he blew up three bridges in front of the German advance, flying a Battle, and used only one bomb each time,” answered my pilot. “ Maybe it’s just another story.” Now that Braddock had been aroused, Pitcairn went on with the briefing. It seemed like an operation which promised very little future for the men who took part in it. FIREWORKS AT THE LOCK. AN hour later, we were cross~ station into which I should |

Taylor’s voice rasped

in the phones. “ Where’s C for Charlie off to ?” he snapped and, when I glanced to starboard, I saw that Braddock had broken away and was going on his own. From that moment onwards, I was too busy to think about Braddock. Ken yelled, “ Fighters!” and I had a glimpse of three Messerschmitt 109’s flash past, apparently on their way to attack our following aircraft. We droned across a flat green and dun landscape with dykes and roads as straight as rulers. Along one of the roads crawled a motorised convoy, seeming to stretch for miles. I did a quick check-up and, unless I'd made a bad mistake, the converging railway lines I could see indicated that we were approaching Nieuval Junction and that the target was five miles ahead. I reported this to Taylor. He said, “ Nice work! You’d better get down now.” I unfastened my safety belt and slid down into the bomb- aimer’s station. I looked down through the bubble of perspex at the ground and had the old queer sensation of floating in space. I saw a huddle of houses, a glint of water and a bisecting railway line. A few moments later, I saw the lock and a tiny target it appeared. Taylor’s voice was calm and unhurried. “ I am going to turn into the target now,” he said. “ Bomb doors open.” “ Bomb doors open!” I answered. From that moment, it ceased to be practice stuff. Tiny pin- points of flame winked below us. The air filled with the smoke smudges of exploding shells. I felt the Blenheim shudder as if it had been flown into an invisible obstacle and then resume its forward progress. I did not blink as I kept my gaze glued to the bomb-sight, my hand on the bomb release button. Smoke wreathed us. There was another crash, another terrific vibration.‘ Our speed increased as Taylor put the nose down and levelled out. We still seemed a long way from the target. I saw a blazing plane, a Blenheim, plunging like a gigantic torch. I saw another staggering away, leaving a trail of oily black smoke. All round us were flashes and puffs of smoke. We nosed in towards the target. My mouth |

| The Rover - 22nd. Feb

1958 - Page 144 was

dry - steady, keep her |

was Braddock who nursed me across the Channel and led me to an aeroclrome. My heart was in my mouth as I pulled the lever to lower the wheels. There was no red light, no warning wail. Unless the warning devices had also packed up, the wheels were down and locked. But, I should have forgotten all about the flaps if Braddock hacln’t flown ahead of me and put his down. Well, I made it. Beginner’s luck, I suppose. I bounced the Blenheim as I pancaked but the aircraft squatted squarely next time and we were home, chased down the runway by the fire- |

tender and ambulance. They got Taylor out and rushed him away. Ken Coe pushed his head out of his hatch. “A bit rough,” he said. “ Once or twice I thought we’d had it.” ' We watched Braddock land his plane amid frantic apprehen- sion from the firemen. They needn’t have worried. He wouldrft have spilled a cup of tea had it been on the wing. He dropped to the ground and pulled off his helmet. “Nice work, George,” he said, unruffled, laconic. “ Where’s the canteen ?I want |

a cuppa.” His navigator, Simley, lowered himself from the cock- pit. He was as white as a sheet and could not control his trembling. ’ Braddock turned his back and strode away in search of the canteen. Simley tottered towards us. His eyes were big and staring. “ He’s crazy, crazy!” he gasped hoarsely. “He flew so low that the blast from our bombs turned us over. We were flying upside down not twenty feet from the ground.” Later in the day, We were flown back to Rarnpton. We arrived to hear that of the eleven Blenheims which had gone out, only five had returned to base and all had been damaged. But, thanks to Braddock, the Panzers were held up. It was on the following morning that the tannoy loud- speakers ordered “ Sergeant Bourne ” to report immediately to the Squadron Commander. Squadron Leader Pitcairn was alone in his office when I went in. “ You did very well yester- day, Bourne,” he said. “ I’m pleased to tell you that the A.O.C. Group has sent his congratulations on your bring- ing the aircraft home---” “ I guess it was the instinct of self-preservation, sir,” I replied. He smiled and then became serious. “ We’re having to shuffle the squadron about,” he said; “ Sergeant Braddock has asked for you as his navigator. Any comments ?” He did not give me the immediate chance of answer- mg. “ Flying with Braddock isn’t everybody’s cup of tea,” he Went on to say. “ Some might think there’s very little future in it.” I was hardly listening. I’d already made up my mind. I got a tremendous kick out of the fact that Braddock had asked for me. “ I’d like to be in his crew,” I said. “You can have a night to think it over,” replied Pitcairn. “No, I’ll go with him,” I said. That was how I became navigator to Braddock. Navigator - to a pilot with a sense of direction like a homing pigeon! It makes me laugh to think of it. Still, what’s in a name ? I flew with Braddock. I found him in the Sergeants’ Mess slinging darts at the dart- board. “ Do you play this game ?” he asked. I gave a nod. I was good at darts. “ The C.O.’s iust had me in to tell me I’m going with you,” I exclaimed. ‘ “ Fine,” grunted Braddock. “ Ready ?” I selected a set of darts. As we were getting ready to play, Flight-Sergeant Harman came in. He was an regular, a hard-bitten looking fellow of |

| The Rover - 22nd. Feb

1958 - Page 145 26

or 27. He sat on the edge of TROUBLE FOR BRADDOCK TOWARDS l9.00 hours, seven |

Group Captain Halder, a

staff officer at Group, and we under- stood he was going to talk to us about Bomber Command’s part in the present emergency. We all stood when Group Captain Martingley, the Com- manding Officer, walked in. When I saw Group Captain Halder I knew I’d seen him before. He had been in our compartment on the journey from Liverpool Street. Squadron Leader Pitcairn and other officers moved to their chairs. The doors were shut. The Commanding Officer briefly introduced the speaker whom, he said, had just returned to England after liaison work with the French Air Force. Halder stood and moved towards the blackboard. “ First of all, I must con- gratulate Squadron I8B on the very good iob they did in destroying the lock at Bous- |

Hitler, the German dictator, from becoming a modern William the Conqueror. We shall halt him, don’t fear that, but only if we pull out all the stops. First, we have to help to get our army off the Dunkirk beaches . . .” I found Halder’s talk of absorbing interest. He left us in no doubt as to the grimness of the situation. Our attacking arm was weak. We had a few squadrons of Whitleys and Wellingtons for long-range probes. ’We were fairly well off for Blenheims, though Coastal Command also needed them, and replacements would be meagre because of the demands of Fighter Command. “ Believe me, you are not regarded as expendable,” he said earnestly. “ It’s common- sense, isn’t it? We are short of machines, and we are short of air crews. You won’t be sent out on suicide

operations, but |

“ Braddock’s been

pinched 1” he exclaimed. I broke into a run and was not far away when the vehicle stopped outside the hut occupied by the Provost Marshal for the area and his staff". Braddock, without a cap and with his hands in his pockets, got out. Two service policemen closed in on him. There was an angry scowl on his face. “ A chap can’t have a game of darts now,” he groused. “ Be quiet!” barked the police sergeant. “Right turn. Quick march!” With Braddock out of step, the three men vanished inside the hut. His few words gave the clue as to what had happened, He had dodged the lecture to play darts at the Hen and Squirrel and had been picked up by the R.A.F. police. It was about half an hour later when Harman came into our hut. “ Where’s Braddock ?” I asked anxiously. “ They’re keeping him,” he said. “ He’s in the cooler. He’ll stay there, too. He’s stretched out his neck a bit too far. The C.O. is hot on discipline. We’ve seen the last of Braddock for a long time.” “ Yes, they might have only torn a strip off him for missing the lecture, but they’ll take a dim view of his breaking bounds!” exclaimed Charlie Black. " I slipped a slab of chocolate into my pocket. I knew Braddock liked chocolate and since he had missed his supper I guessed he would be htmgry. Then I ambled out. By a bit of weaving, I came up behind the brick detention hut without being observed. There were a number of small windows, each covered by a grille. Behind the bars, the windows could be opened for the sake of ventilation. I found three or four bricks to stand on and, by lifting my- self on tip-toe, was iust able to look through the first window. It gave access to a narrow cell. I saw a pair of legs stretched out on the bed. When I tapped the glass, the legs vanished. A moment later, Braddock was looking through the bars at me. When I held up the chocolate he grinned and pulled at the window. It was stiff and, when it did go, opened an inch or two with a rasp. I hurriedly pushed the choco- late through to him. “ Thanks, George,” he said. “ Hurry up and beat it -” I heard footsteps coming and legged it in the opposite direc- tion. As I banked on hard rudder to turn the corner there was a gruff shout of “ Got him,” and a service policeman with a grip like a gorilla flung his arms round me. He’s the greatest pilot of

them |

*

I FLEW WITH

BRADDOCK (Second series) The Rover from 7th Mar 1953

for 22 weeks

I FLEW WITH

BRADDOCK (Second series) The Rover from 7th Mar 1953

for 22 weeks

I FLEW WITH BRADDOCK (Second series - repeat) The Rover from 11th Oct 1958 for 22 weeks

BRADDOCK MASTER OF THE AIR (Repeat of Second series) The Rover and Wizard from 26th Aug 1967 for 22 weeks

Also see my Flickr album - Matt Braddock VC - boys comic stories

| The Rover and Wizard 26th

Aug 1967 - Page 7 STARTING

TODAY. |

From the moment I arrived at Carstock, I had the feeling that I was a square peg in a round hole. Two squadrons of Spitfires used for reconnaissance were stationed there. You don't have to be told that the pilot of a Spitfire flies on his own. There was no need tor navigators there. The Stationmaster was Group Captain Renton and the squadrons were commanded by Squadron Leaders Lambourne and Trayle. Since a sergeant-navigator was of no importance, I kicked my heels about for a couple of days. Then a big excitement or “flap” started. Several of the pilots had been awarded decorations, and a Deputy Secretary of State for Air, Lord Prender— gast, was coming to present the medals. It soon became evident that the officers regarded this investiture as an important occasion, and they began getting every- thing and everybody poshed up. The fuss started with long periods of drill several times a day under the eagle eye of Flight-Sergeant Grimes. To and fro upon the concrete apron in front of the main hangars marched the R.A.F. Regiment, who were to provide the Guard of Honour, and with them everybody else who could be roped in. I was careful to keep out of the way. One morning, however, I was pounced on by Grimes and forced to go on parade. After three days of this misery the morning of the ceremony dawned fine, to the acute disappointment of those who had hoped it would be rained off. The band played and the bayonets of the Guard of Honour flashed as the important visitor appeared in the dis- tinguished company of an Air Vice- Marshal and other brass hats. It was just as the Guard of Honour was being inspected that a Harvard, which could claim to be the noisiest plane in the world, flew into the circuit. |

Lord Prendergast pretended

he could not hear anything, but behind him some scowling faces were looking up. A rocket blazed from the control tower with a woosh and burst into red stars, warning the pilot off. He flew overhead and his plane drowned the band, went round, dived over the perimeter track, pancaked, and taxied from the runway to the side of the apron. During this period the ceremony was held up, since even Flight- Sergeant Grimes could not make himself heard. The engine wheezed, spluttered, and stopped. ,Group Captain Renton, his complexion red with rage, passed on the order that the pilot was to be placed under arrest. I saw the cockpit cover open. A bulging kitbag was dropped on to the wing. A greatcoat fluttered after it, and then a brown paper parcel. |

The pilot who got out was

Matt Braddock in a shabby, unbuttoned tunic, baggy trousers, and shoes without polish. His face was hard and rugged and he had amazing eyes. They were big and luminous as if a lamp were burning behind them. Flight Sergeant Keddy and Sergeant Drax, of the R.A.F. Police, marched towards him. Just as they reached him the band stopped playing and his voice was clearly heard. “ I can’t help it,” he was saying. “ Don’t they know there’s a war on ?” We saw Braddock pick up his kitbag, greatcoat, and brown paper parcel and trudge away with the two R.A.F. police- men. For me, Braddock’s arrival provided the clue as to why I had been posted to Carstock. I would have bet all my cash, which wasn’t much, that we were going to fly together again. |

| The Rover and Wizard 26th

Aug 1967 - Page 8 The ceremonial went on. |

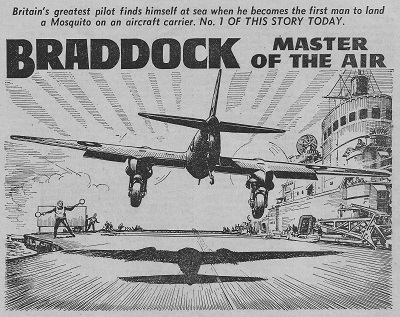

“ It might be the

Mosquito Bomber with that transparent nose,” declared the Station- master. “It will only be a visitor here. It can’t be for us.” The Mosquito glided in gracefully, watched by many admiring eyes. The door slid open. A tall man with dark, wavy hair and an arrogant expression on his handsome face, jumped down. He was wearing white overalls and a striped tie. “ Upon my word, it’s Wayne, Hugh Wayne,” exclaimed Trayle. I knew that name. Who didn’t? It was one of the greatest names in aviation. Wayne was both a designer and a test pilot, one of the leading figures in British aviation. He stood by the plane while Renton and Trayle hurried towards him. His keen gaze swept round. “Where’s Braddock?” he demanded. “ He should be here to take over the plane. Hasn’t he come?” TARGET BERLIN |

them was Braddock. His tunic was unbuttoned and he wasn’t wearing a cap. He strolled towards Wayne. “ Did you get the job done ?” he asked. Wayne nodded. . “Yes, what you suggested was an improvement,” he said. “I told you it would be,” remarked Braddock. Then he beckoned to me. “ Come on, George,” he called out. “You’re in on this.” I hurried to join them by the aircraft. Wayne gave me a casual glance. “ So he’s your navigator, is he?” he said. "‘ That’s right,” replied Braddock, and gave me a wink. I had better put in some- thing about the history of the Mosquito. The Mosquito was of such splendid design that the R.A.F. ordered bomber, fighter, and photo-recce versions before the first Mosquito had flown. It was originally intended as a very fast, unarmed bomber, but it was such a magnificent aeroplane that it served numerous purposes. The first Mosquito Bomber flew in November 1940, the Mosquito Night Fighter in May I941, and the Mosquito Photo-Recce plane in June. For a minute or two, Brad- dock admired the plane. Then Wayne said, “ It’s yours to do the job.” “ If the weather’s right, I’ll do the job tomorrow,” replied Braddock. Wayne’s stare became un- blinking and merciless. “You know the orders,” he snarled. “ If you’re cornered, you’ll put this plane into the ground, put it into the ground so hard that if the Germans spend a year on the job they won’t be able to make any sense of the bits. There’s only one way to make sure of smashing it to atoms and that’s to stay in it and power dive. Remember, if you’re cornered, do that!” “All right,” said Braddock calmly. “Is that okay with you, George?” “Yes,” I replied. Wayne just grinned, then he turned and strode away. With the curtest of nods to the Stationmaster, he headed for the Harvard for his flight back home. “Where are we going, Brad ?” I asked. |

“ Where do you think ?”

he challenged. “Berlin,” I joked. . “George, you're a mind- reader,” he said. It was my turn to look dazed. “By day ?” I gasped. “That’s the idea,” said Braddock. “ We want some proper photos. You and me are going to get ’em. Come on, we’l1 have a trip round so that you can get the feel of the plane.” There were footsteps behind us. The two police, Keddy and Drax, were closing in on Braddock. He gave them a calculating look. Keddy slapped a hand down on his shoulder. “ You’re still in custody,” he snapped. Braddock shook himself free. “Come over here, please,” he shouted to the Station- master. Group Captain Renton was already on the move. “There will be no charge against Sergeant Braddock,” he said to the two police. “ Wait a minute, exclaimed Braddock. “These two cops are to be shut up somewhere by themselves and not let out till George and I come back tomorrow.” “ I can’t do that,” spluttered Renron. , “ I’m not asking, I’m telling you,” said Braddock. “ If you don’t, then the flight’s off.” “Very well,” answered the Group Captain after a pause. I wish I could give a photo- graph of Keddy and Drax when they heard that they were going to be put into solitary confinement. “Aren’t you being a bit hard on ’em, Brad ?” I asked as they walked away. “They might have heard you say Berlin,” retorted Braddock. “ If a whisper leaked out and got to the other side, the Germans would be waiting for us. We have over a thousand miles to fly and, Well, you heard Wayne say what we’ve got to.do if we’re trapped. We’re not taking chances, that’s all.” TEST FLIGHT |

| The Rover and Wizard 26th

Aug 1967 - Page 9 “

It’s tops. I’ve never flown |

compass, which instantly re- corded any change of direction, the air-speed indicator and the altimeter. They would become my business when I was navigating. Then I looked up and uttered a gasp of alarm. “ Your port engine’s stopped,” I exclaimed. “ I was wondering whet you’d n o t i c e,” chuckled Braddock. Then, to my amazement with the port propeller still stopped, he put the Mosquito into a slow roll. ' My confidence in the plane increased when we completed the roll without any loss of stability. In addition to our marvellous view ahead there was a good view astern. l “A Spitfire is chasing us George,” said Braddock after glancing in the rear—vision mirror and then turning his head. “Now you’ll see some- thing.” I guess the lad in the Spit had a surprise. No doubt he was coming along to take a close-up view of a new plane. Braddock’s hand moved on the throttles. I felt a “ kick ” in the back from our accelera- tion. It was incredible, but we were leaving the Spitfire behind in level flight. We went away from it with the greatest of ease. “ Gosh, Brad, there’s nothing in the world to catch us,” I exclaimed. By the time we turned back for base, I had learned the lay-out of the cockpit. I had left my seat and been down to the front compartment to get the hang of things. When we called the ’drome on the radio, the Controller |

stood us off. We saw that at Anson was about to land. “ I guess that Faithful Annie Anson has brought our ground crew,” Braddock said over the inter-com. “It’s a queer set-up,” 1 replied. “ I can understand the Stationmaster being rattled.” “ Believe me it’s necessary,” said Braddock. “ I had a talk with a bloke from M.I.5. He mighty soon convinced me that we’ve taken some hard knocks because some of our chaps couldn’t keep their big mouths shut.” We were told by the Con- troller to pancake. Braddock made a silky landing, and taxied to a bay under camouflage nets. It was there I met Frank and Pete, the mechanics who had come in that Anson, and Harry Howard, who was to look after the cameras. They were to be the new Mosquito’s ground crew. Braddock took me a short distance away from the aircraft. “You go ahead and work out your course for tomorrow now, George,” he said. “ Lock yourself up somewhere with your maps and don’t open the door for anyone less than Winston Churchill himself. DECEPTIVE TALK |

from high levels and the oblique from low. Low level “obliques” of shipping, roads, bridges, defences, etc., were of great value to the ground forces. “Verticals” gave the wider view, and from them photo- graphic maps could be con- structed. Braddock and I were after “verticals,” and We should take them in steady flight from 25,000 feet. I knew this wouldn’t be a piece of cake. We were bank- ing on speed and surprise. We should have to fly dead- straight and level during the operation. Without warning the door opened and Flight - Sergeant Grimes stepped in. “ Get out of here,” roared Braddock, while I hurriedly scooped the maps together. Grimes strutted towards us. Anger reddened. his face. “The C.O. wants you immediately,” he said. I stuffed the maps into my navigation bag. “ Bring ’em along, George,” Braddock snapped. “Don’t leave ’em lying about.” We left the hut and passed through the black-out to the administration buildings. Group Captain Renton waited for us in his office. The Adjutant was with him. Braddock spoke first. “Before anything else is said, sir, I must ask for Flight Sergeant Grimes to be shut up by himself,” he said gruffy. “What are you talking about ?” exclaimed R e n t o n, while Grimes looked as if he were swallowing a lemon. “Tomorrow’s job is off unless you do as I say,” said Braddock. “ He came bursting into our room while we had maps exposed.” Renton gnawed at his lip. He was being asked to shut up one of his most trusted men. “I’m afraid you put your foot in it, Grimes,” he said reluctantly. “ You will be con- fined to your room.” With a scarlet face, and a dirty look at Braddock, Grimes did an about turn and marched out, followed by Hopper. '“I didn’t want to upset the chap, but I want to bring the Mosquito back in one piece,” growled Braddock. The Stationmaster uttered a short, harsh laugh. “The R.A.F. is being |

| The Rover and Wizard 26th

Aug 1967 - Page 10 lectured

about security, but ENEMY COAST |

never left me. I’d

slept with it in my bed. My last glimpse of the ’drome was when Braddock did a broad turn. " “Switch over, George,” he said. I leaned over and turned the petrol cocks from the main to the outer tanks. It was correct to take off on the main tanks, but then to use the fuel in the wing tanks first. “Over,” I reported. I gave Braddock his course and told him we should be crossing the coast in nine minutes. Our plan was to fly low across the Channel, to evade the enemy radar as long as possible, leapfrog in over the French coast, and later to zoom upwards. We were not hurrying. Our speed was no more than 250 miles an hour. It was routine at first, but |

“No,” grunted

Braddock. “ It’s a glint of sunshine on a window.” We swerved, straightened, whisked over the sands, and leapt the cliffs, and if anybody shot at us we didn’t know it. There were thin layers of cloud ahead. Braddock said, “I'm going up,” and drew back the stick. We went up like a rocket. I switched on my oxygen as we continued to climb. The earth dropped away from us. At 25,000 feet we levelled out. I saw three dots away over our starboard wing and flying on a course that would intercept us. . “ Huns, Brad I” I exclaimed. “Messerschmitt 109’s,” he said as calmly as if they were pigeons. I hoped he had cause to be calm. The Me. 109 was the fighter most respected by our fighter pilots during

the |

farther and farther over

enemy territory. The silver thread below us was the Rhine. We kept away from the industrial haze hanging over the manu- facturing areas. Towns meant anti-aircraft guns. The country was green and featureless. We picked up the landmarks we had fixed, a railway junction, a lake, a wood. I took a look at my map of Berlin. Ruled on it was a rectangle. It respresented the area that we wanted to photograph. We had worked out that we should need three runs across the area to do the job. . Then I did. a check on our position. “ Berlin eight minutes ahead, Brad,” I said. “Okay,” he answered. “ Better look after your cameras now.” ' I unhitched myself and got down. The camera controls took the place of the bomb- release apparatus. There was nothing between me and Germany except a panel of glass. My shoulders were against the curved plywood wall and my legs stuck out of the compartment. The two cameras were adjusted so that. the area photo- graphed by one slightly over- lapped that covered by the other. The film moved as in a cine-camera, but with an interval of three seconds between exposures. Each photo- graph had a big overlap over its predecessor. I checked over the gear, gave each camera a brief run, and saw that the correct speed was indicated on the gauges. “ Berlin!” growled Braddock. While I had been busy, we had closed up on the sprawling city. I wondered how could the gunners miss us as we flew straight and level? Braddock seemed to read my thoughts. “ Put yourself in their shoes, George,” he said. “ We’re just a dot in the sky to them.” I picked up our pinpoint, a railway bridge across a canal. “Target coming up,” I muttered, and started the cameras. Braddock and Bourne are off |

*

*

|

I Flew With Braddock-3 for consistency

– actually titled… BRADDOCK FLEW BY NIGHT (Third series) The Rover from 19th Sept 1953 for 11 weeks BRADDOCK FLEW BY NIGHT (Third series - repeat) The Rover and Wizard from 11th May 1968 for 11 weeks Also see my Flickr album - Matt Braddock VC - boys comic stories |

*

| The Rover and Wizard 11th

May 1968 - Page 2 Many,

many readers have asked for another story about the R.A.F.’s

No. I pilot, HERE I am again, writing about the war-time exploits

of one of the |

I had flown with Braddock in

many diiferent types of aircraft and on over a hundred missions. First of all, we were in Blenheims and Hampden bombers and took part in many raids on the barges Hitler was assembling for his I940 invasion of Britain that never came off. Then, when the German raids against Britain were at their height, we were switched to the Beaufighters and had our share of stalking and destroying the German bombers at night. After that we were given one of the first Mosquito fighters and were used to try out rockets, the new weapons. Our last flight with a Mosquito showed Braddock’s uncanny ability for finding a target. We were in our hut at Wanborough Aerodrome that afternoon. The door flew open and an aircraftman dashed in. “ Could you get over to Flying Control?” he panted. “ I don’t know what’s happened, but there’s a big flap on. The armourers are rushing rockets over to your plane.” Braddock fetched his flying coat off the peg and picked up his helmet. “ We’ll go and see what the excite- ment’s about, George,” he said. Twenty minutes later we were airborne and headed seawards in search of a German submarine--a U-boat—-that was known to be limping on the surface towards the port of Brest after a bombing attack on it by a Sunderland flying-boat. We knew the position in which the U-boat had been attacked by the Sunder- land, and it was estimated that its speed after that was ten knots. The clouds were low. We flew through |

rain which cut down

visibility to less than a mile. It was a day when sensible birds would have walked. Even as low as a thousand feet we flew in and out of dirty cloud. Braddock asked for our position and I gave him my estimate. For a moment he considered it. “ No, you’re a bit out, George,” he said. “ You haven’t allowed enough drift. The wind’s stronger than you think.” I added ten knots to the estimated speed of the wind and gave my correction, “ That’s more like it,” grunted Brad- dock; “ We shan’t be far out.” “ I don’t fancy our chances of finding the submarine,” I said as we were struck by a squall. We roared on. It was blind flying most of the time. I stared into the haze and reckoned we might as well have stayed at home. Braddock’s voice crackled on the inter- communication set. “ Arm the rockets, George,” he said. “ I reckon we’re getting hot.” Braddock tipped the Mosquito over in a tight turn. In the gloom there were sudden flickers and flashes. Braddock chuckled grimly. “ Somebody is shooting at us, George. They’ve heard us coming.” Ahead of us I saw the shape of a trawler, and beyond it the slate-coloured U-boat. There were flashes both from the trawler and the conning-tower of the submarine. We whirled away, turned, climbed a few hunmed feet, and then dived. Braddock pressed the button and I saw the salvo of rockets, leaving fleecy trails of smoke, striking the U-boat. Eight sixty-pound warheads punctured the skin of the submarine and exploded inside its vitals. We saw a terrifc sheet |

of flame shoot up from the

cunning- tower of the doomed U-boat and turned away. Braddock broke radio silence and called base. _ “Found it, sunk it,” he said. “ Our time of arrival is seventeen-thirty. Put the kettle on.” At half-past five in the afternoon - or seventeen-thirty to the tick—-we pan- caked at Wanhorough. Five minutes later, when we were having a drink of tea, Braddock received a message that he was wanted on the phone. He gulped down the rest of his tea and went to take the call. I went over to our hut. An envelope was waiting. It contained a pass to allow me to go on leave. Braddock catne striding back. “ I’ve just heard on the phone that I’ve to go to London, George,” he said. “ We can travel together then,” I exclaimed. Braddock nodded. We travelled to London together and I walked with him to the Air Ministry. Braddock grinned at me. “ This is where we say cheerio for now, George,” he said. “ I’ll go and see what the chap wants. It’ll be about some flying job for me, but whatever happens, I’ll be wanting you to be in it as my navigator.” Braddock went up the steps, and it suddenly struck me that few sergeants would enter the Air Ministry with a tunic unbuttoned and a cap stuck under the shoulder-strap. Braddock was always a chap who gave no thought to the little rules and regulations. No sooner did he get his nose inside the door than he was pounced on by a glittering flight-sergeant with a waxed moustache. “ Where have you come from, the nearest gutter?” the flight-sergeant snarled. “ What’s your name ?” “ Braddock !” A Flight-Lieutenant hurried across the vestibule. |

| The Rover and Wizard 11th

May 1968 - Page 3 “ Come with me, Sergeant CHANGE OF |

classes assembled in the

hall. He then brought in a civilian. “Help, it’s that Boflin again,” muttered one sergeant- navigator who had been put back to take the course again, having failed in the examination. Wing-Commander Raught demanded silence. He then introduced Dr Stanhope Studley, and the Boffn stood, took a sip from the glass of water on the table, and began to talk. “ I am here this afternoon to talk about Gee, an instrument which you will shortly be using,” he said. “ Our aim has been to provide you with the means of bombing accurately even when the ground is hidden by cloud.” He stood with his hands behind his back and I wondered if he’d ever flown in an aircraft through cloud, rain, and fog. “With the aid of Gee we shall be able to attack seven times more often than before,” he stated. The room was stuffy and I just could not keep my eyes open. The next thing that happened so far as I was con- cerned was a hard prod from my neighbour. “ You’re booked for going to sleep,” he whispered, and I became conscious of the Wing- Commander’s angry stare at me. “ He’s taken your name.” After another half-hour of dreary talk Dr Studley reached |

the end of his lecture. He

then asked for questions. I thought I could perhaps get away with the explanation that my eyes had been merely closed if I asked an intelligent question. “ What’s the range of Gee, sir?” I exclaimed. Dr Studley gave me a cold look. “ I dealt with that in the course of my talk,” he snapped. “ I will, for your benefit, repeat that Gee has an extreme range of four hundred miles. A range of three hundred and fifty miles will be enough to make sure of accurate bombing of the industrial area of the Ruhr, in West Germany.” Within five minutes of the end of the lecture I was stand- ing on the mat in the Command- ing Officer’s office. I had a row of medal ribbons including those of the D.F.M. and the D.S.M., the latter awarded by the recommenda- tion of the Navy for assisting Braddock in bringing a hard- hit motor launch back from Norway. “The trouble with people like you, Bourne, is that you get ideas of your own impor- tance,” snarled Raught. “ You will be put back to start the course again next Monday. Week-end leave, which was to have been granted you, will be cancelled. Dismiss!” I marched out of the office feeling wild. On the following morning there was a class on navigation by the stars. It was taken by Flying-Officer Taft, who never |

used two words when he could find ten to say the same thing. He was nattering away when a motor cycle came roaring up the drive of the large house where the school was held. The motorbike stopped and its hooter screeched. I looked through the window. The rider, still astride, pulled his goggles down and I saw the rugged face of Braddock. He gave the hooter another squeeze. He was in R.A.F. uniform Without a cap. “ I know him, sir,” I ex- claimed. “ He’s Sergeant Brad- dock.” “Then go and tell him to report to the flight-sergeant that he has interrupted classes,” snapped Taft. I hurried out. Braddock grinned. “Hurry up and get your things, George,” he said. “I don’t want to hang about.” I looked at him in surprise. “ I have to stay here for at least another three weeks,” I exclaimed. “ I haven’t been posted anywhere yet. In fact, I’ve fallen out with the Wingco and he’s set me back to begin the course again.” There were clattering foot- steps. Out of the house hurried Flight-Sergeant Prattley and just astem of him was the Wing- Commander. “ Stop that din !” snarled Prattley. |

| The Rover and Wizard 11th

May 1968 - Page 4 “

Return to your class, |

meter, and, as we were doing ninety, no doubt he was right. BRADDOCK’S CREW |

improving. The Whitleys and Hampdens, which had done such a good job, were being withdrawn. The four-engined Halifax and the Wellington formed the bulk of the bomber force. The Lancasters were just beginning to arrive in useful numbers. That day Braddock and I had been on the road for a couple of hours and were speeding down a long straight road in Sussex when Braddock closed the throttle and braked. I heard the roar of engines. We gazed up at a big black bomber that was flying at no more than a thousand feet. “There you are, George,” exclaimed Braddock. “There’s a Lancaster. It’s a real aero- plane. It’s a treat to handle.” “ So you’ve been flying Lanks,” I said. “ I’ve done a short course in ’em,” Braddock replied. “ After it finished I received my post- ing to Craxby.” He pushed off again. We sped along for another half- hour. The roof of a big house was just visible among trees at the side of the road. As we passed the end of the drive I saw a couple of R.A.F. sentries. “ We’re nearly at the drome,” Braddock exclaimed. “ That house will be Group Head- quarters.” ' “ Who’s the Commanding Officer, Brad ?” I asked. “ A bloke called Air Vice- Marshal Pringell,” Braddock responded. “ He has a good reputation.” We saw hangars ahead. We ran alongside the barbed wire fence at the side of the drome. A Halifax was taxi-ing along the perimeter track. I saw a Lancaster on the ground. Braddock turned into the gateway and stopped opposite the guardroom. A corporal came up to us. “We’re joining the Lan- caster squadron,” Braddock re- ported. ' “ I’ll have to see your papers,” replied the corporal. “ You can see mine, but George’s posting hasn’t caught up with him yet,” said Brad- dock. “ It’ll be all right. We’ll go and see the Adiutant.” “ I’ll have to escort you,” rapped out the corporal and eyed rne suspiciously. Braddock parked his bike and the corporal marched with us to the administration block, |

a long brick building well away from the hangars. There was a lot of activity. A fuel bowser rumbled past us. A yellow tractor hauled a string of trailers-—these were for transporting bombs to the planes. The Halifax we had seen on the perimeter track reached the runway and picked up speed for the take-off We were taken into an ante- room. The corporal went on into the office. of the Adjutant, Flight-Lieutenant Parr. Then we were called in. , It was a very tidy office. Everything was in its place. Parr looked very neat and tidy himself. His complexion was pale and he wore spectacles. “ Which of you is Braddock?” he snapped. “ Me,” said Braddock. “ I’ve brought George Bourne along because I want him as my navigator.” . " This is all wrong,” barked Parr. “ I’ve had no posting for Bourne. I’ve never even heard of him.” Another door opened. A Squadron-Leader looked in. He looked young to have that high rank, but the ribbons on his breast showed he had been awarded the D.S.O. and the D.F.C. This was Squadron- Leader Devenish, commanding Squadron 57A, which was com- posed of Lancasters. “ Ah, Braddock, I remember you from the days we flew Blenheims,” he said, sticking out his hand. “It gave me a big kick when I heard you were joining us” He fixed his gaze on Braddock’s shabby tunic. “Where’s your V.C. ribbon ?” Braddock shrugged. “ I haven’t got around to stitching it on yet,” he said. “Three months is a long time to get round to it,” ex- claimed Devenish. “ Braddock’s brought his own navigator without any official permission, sir,” Parr blurted out. “ Whew, you can’t do things like that,” gasped Devenish. “ I’ve done it,” said Brad- dock. “ George Bourne has flown with me on over a hundred sorties and he’s the chap I want.” Devenish glanced through the window. Group-Captain Larke, a tall, erect man with a sharp pointed chin was walking |

| The Rover and Wizard 11th

May 1968 - Page 5 briskly

towards the administra- TARGET FOR |

to walk away. It had a wing- span of I02 feet and the bomb doors had a length of 33 feet. The bomb bay could carry a load of 20,000 lb. and the four engines had the power to fly high at a speed of 300 miles per hour. Braddock was pleased with his new plane. “ It ticked away like a clock,” he remarked. As we made for the canteen we formed a straggling pro- cession. Our crew numbered seven. The radio-operator was Nicker Brown, whose home was in Northampton, and the two gunners, Hoppy Robinson and Les Howe, both belonged to London. Their age was about twenty. We were all sergeants in F Fox, but in bombers you could have all ranks mixed in an aircraft. The Lancaster K King had a sergeant as pilot and a Flight Lieutenant as rear gunner. Rank didn’t count in an aircrew—the pilot was always the captain. We were drinking tea and eating buns - Ham complained that the currants in his bun were made of black lead—when the loudspeaker of the tannoy was switched on. The tannoy was used for announcements to be made all over the drome. The order was for the pilots and navigators of the Lancasters to go at once to the briefing- room. The first person we saw when we entered the room was the Air Officer Commanding, Air Vice-Marshal Pringell. He had the reputation of being a fighting airman and he was famous for his bad temper. He had a determined mouth and a brusque manner. The second person I saw took me back to my days at the navigation school. Dr Stan- hope Studley was with us. The Stationmaster and the squadron commanders were, of course. in the room. _ The moment the door was shut the A.O.C. spoke. “ Your target will be Essen", he rapped out. He let the name of the famous German industrial town sink in. “ The great Krupps factory is in the middle of Essen,” he exclaimed. “ So far, we haven’t hit it.” He paused again. “ Essen is a large town but a difficult target,” he said. “Visibility is always bad be- |

||

| The Rover and Wizard 11th

May 1968 - Page 6 cause of the smoke from factory THE RAID ON |

ing. May we take off, please? Over !” “ O K! Take off!” The roar increased. Braddock released the brakes and there was such tremendous accelera- tion that I nearly went over the back of the seat. We went thumping along till, with the air-speed indicator showing 110 miles an hour, the motion became steady. We were airborne and on our way to Essen. Braddock and Ham ex- changed the routine iargon. “ Climbing power, wheels up, flaps up, cruising power.” The air speed settled down at 210 miles an hour. I came into the picture when I

gave |

Just so that they wouldn’t feel lonely in their gun turrets, he called Hoppy and Les. Hoppy didn’t reply on the dot and Braddock demanded, “ Are you all right ?” “ Sorry, I had my mouth full,” said Hoppy and, judging by his splutter, a crumb had gone the wrong way.” “ You’ve started early,” chuckled Braddock. I took another Gee fix. “ Enemy coast ahead,” I exclaimed. Half an hour later we were flying over broken clouds. Through every gap glared the searchlights. They were dazzling. There had been one or two salvoes of anti-aircraft gun- fire, but the heavily-defended areas were still I5 minutes fly- ing distance. I took another Gee fix. I plotted our position and compared it with the course I had set. The clouds opened. The searchlights blazed through. I saw flashes flicking across the sky. The ominous red winks got nearer. Braddock started to weave. I watched the movements of the compass and the air speed indicator. We were lit up in the, glare. There was no evading it. We had to go through that glare. Braddock’s voice ripped over the inter-com. “ Fighter two o’clock and above,” he snarled. “ Hold your hats on.” I was crushed by the pressure of centrifugal force as our Lancaster made a quick turn. The note of the slipstream screeched shrilly. I saw things blurred by the red veil over my eyes. The pressure eased off. I shoved my oxygen mask, which had dragged down, back over my face and gulped to fill my lungs. “The German fighter has lost us! He went the other way,” Braddock said. “ Where are we, George ?” I tried to get it from Gee, but the signal was weak and confused. “ Come on,” growled Braddock. “What’s happened to Gee?” “ The signal’s weak and wonky,” I said. “ By my own reckoning we’re ten miles south-west of Essen.” Over the air, with his voice crackling through the howls and |